Bill Bryant is a partner at the venture firm DFJ (Draper Fisher Juvertson). He has had early involvement in more than 25 leading software companies, serving as founder, senior exec or investor. Some notable companies include Hotmail, Z2live, Qpass, Netbot, Isilon, Remitly and Socrata. He shared his thoughts with Capital & Growth’s Jasper Kuria in the interview below, first published by TechCrunch.

Pundits are painting a picture of doom and gloom for startups, saying it will be harder to raise money. What do you think?

I think the next several months and possibly years will be challenging for raising capital. There has definitely been a reset. The market was over extended in an unhealthy way and we are seeing the impact.

The catalyst for this reset has been the collapse of public markets stocks where comparisons versus private startup companies are unfavorable.

Smart investors are saying: “Why would I invest in this promising startup that values itself at 10 to 15 x revenue when there are fantastic companies trading for 3 x revenue. It doesn’t make sense.”

Does that mean we should all throw up our hands? Absolutely not. We invested in Chef in January 2009, six months after the collapse. It was a great time. They started small with four co-founders. A year after, the company was 8 – 10 people and we raised a responsible $3.75 million to get started. Great companies were created in that time frame just like they will be today.

The good thing about a market like this is it doesn’t attract the wannabe tourist entrepreneur.

Adam Jacob, CTO of Chef (formerly Opscode)

Some investors are saying that in the current climate, many privately held companies will have to reset their valuations in order to raise money and survive. If you were an early investor in such companies, what would you advise them to do?

That is the harsh reality. Unless you can round up necessary capital internally and keep valuations just for optics, new investors will only do deals at lower prices.

There is just no way around that especially where companies stretched to get to a valuation that wasn’t warranted, often times giving up term concessions.

Valuation alone doesn’t mean much. Many entrepreneurs agreed to onerous terms to get a unicorn-esque valuation and that’s really hard.

For example, as an investor I could say, fine, I’ll give you your billion-dollar valuation as long as I get 3x senior liquidation preferences on my $10 million. This means my only bet is that your company is worth $30 million. In the event of a sale, I get $30 million first before the entrepreneur gets anything.

Valuation alone doesn’t mean much. Many entrepreneurs agreed to onerous terms to get a unicorn-esque valuation and that’s really hard. Any new investor coming into the deal must radically discount the valuation. I always advise entrepreneurs to set realistic valuations at each stage.

In the past, you said you only invest in companies pursuing transformative innovation (versus those doing ‘fluffy’ stuff like social media). Do you still hold this view? Investments in clean tech and renewable energy have disappointed, while Facebook and Twitter are some of the most successful IPOs in recent times.

As venture investors it is incumbent upon us to identify enduring and iconic companies that are addressing large scale challenges. This is DFJ’s philosophy. We have been investing in technology for 31 years and we identify entrepreneurs who are disrupting and innovating in large scale industries.

Two examples include SpaceX and Telsa where we’ve had successful partnerships with Elon Musk. These are the kinds of opportunities in which you can create true value and build billion dollar companies.

You make a good point that clean tech and renewable energy have disappointed. We spent a lot of effort trying to make that work in the 2000’s and learned that these markets are not a venture asset class.

The clean tech area in particular, you could demonstrate a new technology for venture dollars but the production and scale up was hundreds of millions of dollars and therefore not a great venture asset class.

The clean tech area in particular, you could demonstrate a new technology for venture dollars but the production and scale up was hundreds of millions of dollars and therefore not a great venture asset class.

You asked a question about Facebook and Twitter. I view those as transformative companies as well. While they are not hard-tech, the scaling up of a company like Facebook is an incredible engineering feat. It is not just fluffy social media.

Based on your comment about investing in Chef right after the bubble burst, is your strategy swooping in and finding the bargains or sitting out the market until prices stabilize?

There is no bargain hunting strategy in venture capital. You just try to identify the most promising companies and the entry price has not historically mattered. People were thinking investors were crazy to value Facebook at $100 million to $50 billion. Today they are valued at $400 billion?

You have said in the past you don’t have a thesis or theme when investing. Why?

Yes, I don’t invest in themes; rather, I invest in amazing entrepreneurs. There are thematic investors and sector-specific investors. I am not thematic because, by the time investors like me start prognosticating on what they think is interesting, the time to make those investments is probably 18 months in the past.

We are not deep enough. We are not domain experts. We are not living the problems the way the entrepreneurs do. Great entrepreneurs are obsessed about these problems for years in many cases. They are purposeful, mission driven and have direct visceral experience with the issues.

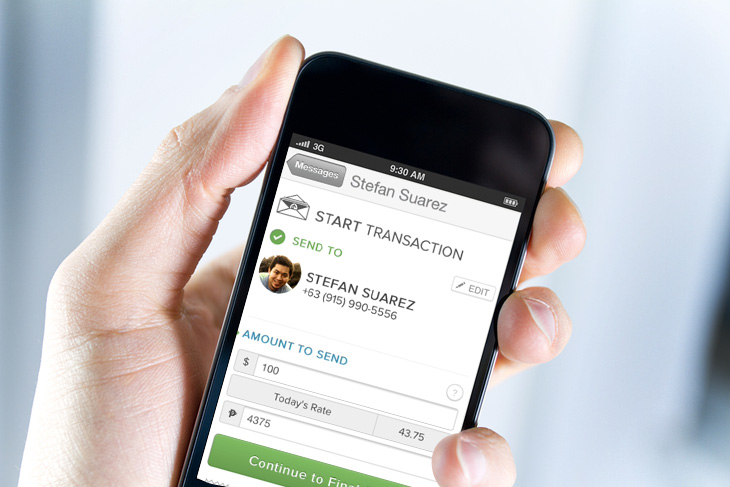

the Remitly team

For example, Remitly. Matt Oppenheimer spent 4.5 years in Kenya as a bank manager for Barclays and watched firsthand the challenges that the local population had in receiving money from loved ones abroad. He watched this process play out day-in and day-out said, ‘“I can fix this. We can build technology to these transfers more efficiently”. He then came back to the States and joined the TechStars accelerator program, at the end of which Remitly emerged.

This is an individual who started the company from a deep desire to transform how hundreds of millions of workers around the world send and receive money.

In contrast, it would be ridiculous for me to say “remittances is a $600 billion market and is ripe for innovation. Let me see how I can disrupt it”. Matt lived this and thought about it for years. That is the kind of entrepreneur we back.

The investment strategy you’ve explained (about finding people who have lived through and thought deeply about problems) seems really sound. Would you say thematic and sectoral investors are wrong?

I don’t know that they are right or wrong but what they end backing is people who are opportunistically drawn to sectors. They are reading analysts and saying ‘that’s a hot sector’. They don’t have the deep passion it takes to create great companies.

To build a great company, there are many ups and downs. If you are not 100% obsessed with the problem you are solving, it is disheartening and you’ll want to give up.

Chef is another example. It started out as an open source project written by Adam Jacob, a sys admin. He was just solving his own problem of “How do you manage servers at scale? The existing tools were crap, so he decided to solve the problem because he faced it daily.

What are three things that turn you off when an entrepreneur or company pitches to you?

I only have three? God, where do I start? First, I never thought startups were formulaic, that you say these three things and then you get funded.

What you are trying to judge is does the entrepreneur have this reality distortion field around them and also a sense of what is possible? They need to be visionary and project 7 – 10 years and yet also grounded enough to say ‘here is how we start in the next 6 – 12 months.’

I’ll use Remitly as an example again. Yes, it is a $600 billion market. Can you address it on day one? No, you can’t. It is not possible to even get licenses to operate in all of these markets, so what is a thoughtful approach? That is what Matt brought to the table.

He had a broad understanding but he took a Mckinsey-esque approach to dissecting it. This is a market where your success in the Philippines doesn’t carry over to Kenya. There is no overlap of the population so it is a separate customer acquisition and education process.

So both execution without vision and vice-versa are turnoffs.

A second turn off is a basic lack of understanding of business models. I see plans where they say “In my third year I am going to have 78% net margins” or “I am going to drive $50 million in revenue and $42 million in EBITDA” There is no business in the world like that yet we hear these type of pitches.

Entrepreneurs need to appreciate that venture capitalists have a business model too.

The third would be the entrepreneur not appreciating that venture capitalists have a business model too. We don’t know apriori which companies will be successful and so for every 10 investments we make, the one or two runaway successes must pay for all the failures.

We then price the valuations accordingly. If the entrepreneur is asking for $5 million and projecting a $150 million exit, I need to own a third of the company ($50 million) to get my 10 x or better return. Often, entrepreneurs view us as banks and think we can make do with 6% returns.

If you were to pick one and only one single biggest factor that determines a startup’s success, what would it be? (The three most common answewrs I hear are product-market fit, timing, and team). Earlier, you suggested it would be an amazing entrepreneur. Would that be your factor?

Yes, but amazing entrepreneurs do a couple of things. They pick the right market and the right problem. They also hire a great team, create a sense of mission. Lastly they are culture masters.

If I were to pick one thing, it would be culture because companies are compilations of individual people who wake up every day and decide I am going to work for company X versus not. Why do they do that?

Compensation plays a part but at the end of the day if you are going to spend 10 to 12 hours a day at a place of work you’ve gotta be inspired by what the company is about. At Remitly, the people feel that in some small way they are changing the world and feel good about it.

Do you have any parting thoughts for entrepreneurs?

Pursue a startup where you care about the outcome deeply. Startups are inherently hard. If you are successful at a startup you won’t know that for generally 5 – 7 years.

Also, pursue a big problem. A small business is as hard or harder than a big-idea business. It is harder to attract people and resources. All things being equal, pursue a big idea even though on the surface it might seem like a smaller one might be more certain.