The Story of Toothpaste. How It Became a Mainstream Product

Introduction

The Pulitzer-award winning reporter Charles Duhigg presents to us an interesting read about a subject that often defines our daily routine- habit. In his 2012 New York bestseller, The Power of Habit, we see a ubiquitous read that has been recommended by readers across the divide. Duhigg presents to us truths and techniques on how habits form and even goes out of his way to give us insight on how to change them.

The Power of Habit examines and recounts some important illustrations on the role played by habits in individuals, societies, and organizations. The book further goes out of way to provide practical techniques to identify and subsequently direct the cues that actually control our behaviors as well as results. A read between the lines of this book will definitely illuminate your perspectives and understanding of habit formation and a blueprint to changing them.

The book uses various stories and cases to give its readers an in-depth look into the concept of habit formation and how the characters in the story struggle to change them. The book can therefore be broadly classified in three parts: The Habits of Individuals, The Habits of Organizations and The Habits of Societies.

Part One: The Habits of Individuals

Chapter 1: The Habit Loop: How Habits Work

The first story in the book is that of Eugene Pauly, a 71-year old man who suffers from viral encephalitis, which makes him lose the medial temporal lobe of his brain. Astonishingly, the condition left the rest of Eugene's brain intact.

The resulting effect is that he could clearly remember anything that occurred prior to 1960, and on the flip-side, he had short term memory for recent events. In that state, he could not retain memory of newer occurrences for more than a minute with a habit of constantly repeating words. He neither could remember his children, where he was and where basic installments like the kitchen or his bedroom were.

Eugene's wife became concerned and decided to make him get some exercise by taking him for a walk around the block every day. One day, Eugene disappeared making his wife worried and frantic but luckily he showed up fifteen minutes later. It just happened that Eugene had, that day, taken the routine walk all by himself.

He soon made it his daily routine to take the walk around his house by himself. This occurrence startled scientists as Eugene had started to prove what they had been suspecting but never before proved: that the part of the brain where habits are performed and operate is entirely separate from the part of the brain responsible for memory. It was later confirmed that we can learn and make choices without having to remember anything about the process of decision making or the lesson.

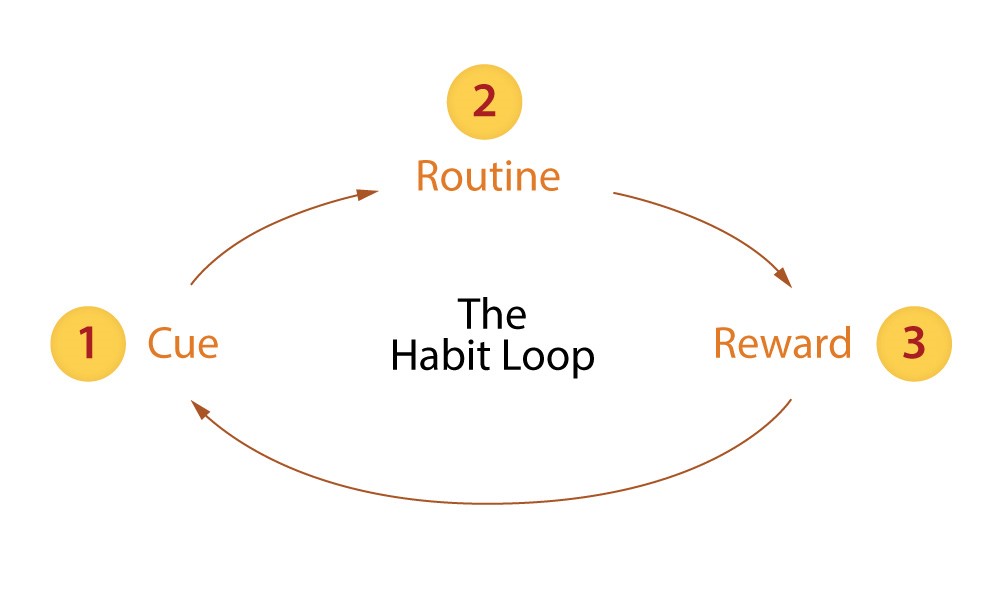

The habit process, Duhigg argues, is a loop that has three steps:

1. Cue – it is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode, and which routine to use.

2. Routine - this is a physical, mental, or emotional behavior that follows the cue.

3. Reward – this is a positive stimulus that tells your brain that the routine works well, and is worth remembering.

Simply understanding how habits work makes them much easier to control. By learning to observe the cues and rewards, we can change the routines.

Chapter 2: The Craving Brain: How to Create New Habits

The Pepsodent Story

It is surprising that in the early 20th Century America, people hardly brushed their teeth; a fact that is best explains the nature of early World War veterans' rotten teeth. This state of deteriorated dental hygiene led the federal government to declare it a national security risk.

All that changed when an old friend convinced Claude Hopkins, a marketing genius that he could apply his marketing skills to sell toothpaste. Hopkins had earlier been responsible for bringing unknown products such as Quaker Oats and Good Year into the limelight turning them into household names.

Claude Hopkins signature marketing technique was anchored on tapping the habit loop and setting it to depend on a specific trigger without regard to their connection. A preposterous conviction that Hopkins managed to set on the American market is that of Quaker Oats. He managed to convince America that the product provided 24-hour energy if, only you took a bowl each morning.

Hopkins decided to follow an identical blueprint to turn toothpaste into a national habit -and with it, Pepsodent. The wording on his ad read: “Just run your tongue across your teeth. You’ll feel a film – that’s what makes your teeth look ‘off-color’ and invites decay.” His ad had images of smiling people with beautiful white teeth which seemed to reinforce the cue on which he would anchor his marketing.

The ad further read: “Note how many pretty teeth are seen everywhere. Millions are using a new method of teeth cleaning. Why should any woman have dingy film on her teeth? Pepsodent removes the film!”

The last claim was outright untrue as the 'film' he alluded to in the advertisement is a naturally occurring membrane which cannot be removed by toothpaste. However, Hopkins managed to identify a universal cue which he tied to a reward - beautiful teeth. People bought the connection of the cue to the reward and in a span of one decade, 65% of the population had adopted usage of toothpaste, up from 7%.

Duhigg contrasts Hopkins' Pepsodent success with the abysmal performance of P&G's Febreze when it entered the market for the first time. The problem Febreze were trying to solve is the phenomenon of the olfactory system that makes people get used to a smell thereby losing the ability to detect it.

In terms of functionality, it was a legitimate technological advancement and it worked like a charm. The lady with nine cats and house odor lacked sufficient cue to induce her to buy the product which would have effectively transformed her life.

P&G executives arrived at a decision to axe the product but the product management team discovered that a habit is formed when the brain anticipates a reward the moment a cue is introduced, before the routine is even completed. It is difficult to sell a product that provides scentless-ness without a cue for the brain to anticipate it.

P&G began marketing their product instead as an air freshener- a product used to give a room a pleasantly aromatic feel- and with it, sending Febreze sales through the roof. People who tried the product became hooked to the smell from Febreze's finishing spritz. P&G would later mention the actual value of the product by explaining how the product truly works - by eliminating odors, rather than covering them up.

Authors argue, using the story of Febreze, that Claude Hopkins' techniques really had little impact on the sales of Pespsodent toothpaste. Plenty other toothpaste companies had been using similar techniques and in reality, Pepsodent's success had been accidental. With no foresight for the impact of their choice, they had used mint oil and citric acid amongst other ingredients therefore creating a cooling and tickling effect. It is that feeling which created a cue that people missed when they forgot to brush their teeth.

Chapter 3: The Golden Rule of Habit Change: Why Transformation Occurs

Tony Dungy transformed the game of American football using a counterintuitive approach to football coaching. Tony chose not to focus on outmatching his opponents with golden playbooks or complex schemes, but on drilling his team on a few key plays. He solely focused his efforts on training his team to react based on habit and stop thinking.

The coach knew that it is usually difficult to overcome habits and instead, it can only be changed when a new routine is introduced and successfully inserted into the process bearing the same cue and its matching reward. He therefore trained his team to automatically link the cues they had already learnt to various on-pitch routines involving less complexity, less choices, and more subconscious reactions.

With this approach, Tony turned two abysmal teams to championship contenders in quick succession.

Tony Dungy changed the game of American football with a counterintuitive coaching approach: instead of trying to outmatch his opponents with thicker play books and complex schemes, Tony drilled his team on only a few key plays. He did everything he could to get his team to stop thinking, and react based on habit instead.

The most famous and widespread case of a successful habit change is perhaps the 12-step Alcoholics Anonymous program. The fact that a physical addiction with genetic and psychological roots is often overcome by an unscientific, unstructured arbitrary system is something that the author finds to be fascinating.

More intriguing is that this system addresses neither the psychiatric or biochemical factors that are considered the foundation of alcoholism. Alcoholics Anonymous program first inserts a new routine into the cue/reward process by identifying the need to be fulfilled by alcohol - relaxation, anxiety, companionship, escape - and provides a similar relief through the Alcoholics Anonymous group.

However, the program alone cannot suffice to keep the alcoholics from falling off the wagon when the factors triggering the habit reach boiling point. Belief is a crucial element in habit change and it emanates from an individual making change possible. The author quotes Todd Heatherton, who authored a study of the power of Alcoholics Anonymous program’s method at UC Berkeley: “Change occurs among other people. It seems real when we can see it in other people’s eyes.”

Two: The Habits of Successful Organizations

Chapter 4: Keystone Habits, or The Ballad of Paul O’Neill: Which Habits Matter Most

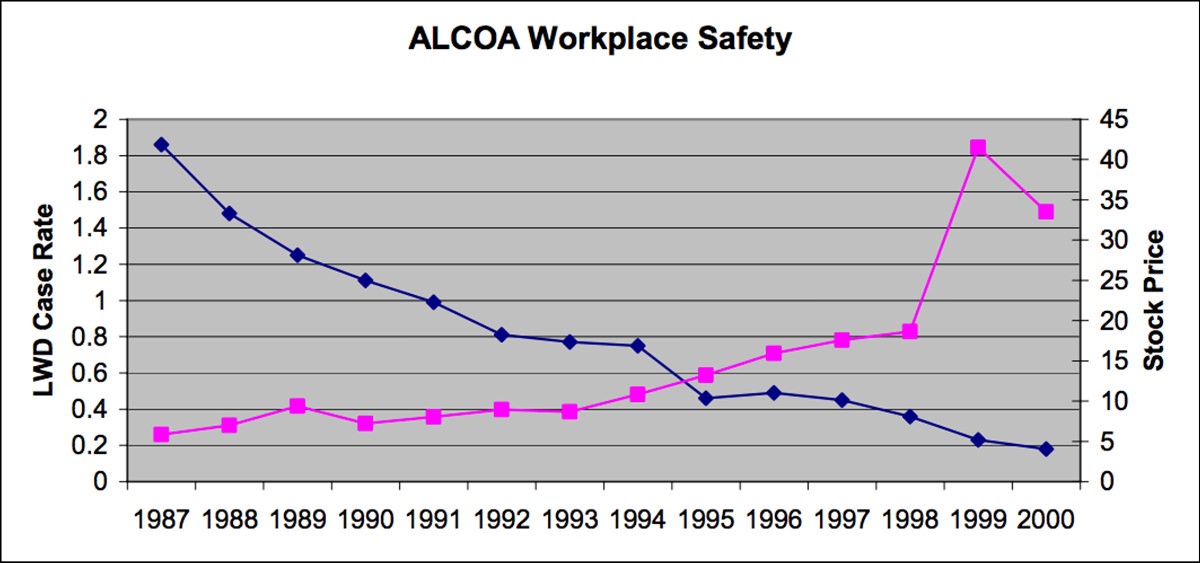

New CEO's often follow a standard script about costs and profits, the evils of government interference, and a promise to implement various business buzzwords. In October 1987, the new CEO of Fortune 500 manufacturer Alcoa, Paul O'Neill stepped on the stage to give his maiden speech to investors.

Contrary to the standard script followed by new CEO's, he perplexed his audience by his opening remarks; "I want to talk to you about work safety." He then went on to expound his vision of making Alcoa an injury-free workplace and proceeded to point out the fire exits in the room while instructing the audience on their use in case of emergency.

As you may have guessed it, Paul succeeded immensely in his quest for an injury-free Alcoa bringing down the rate of work injury from at least one-a-week to to one-twentieth of the national average in eleven years. Of interest however, was that Alcoa's income rose by 500% and subsequently its market capitalization by $27 billion.

Paul was immensely successful in his stated safety goals; by his retirement eleven years later, Alcoa went from having about an accident a week at each plant to boasting a worker injury rate that was one-twentieth the national average. More interestingly, however, Alcoa’s income had risen 500%, and its market capitalization had increased by $27 billion.

O'Neill took over the job at a time when Alcoa was criticized for poor quality and a slow workforce. This came after his predecessor failed terribly at mandating quality improvements which resulted in a 15,000 - employee strike. O'Neill reckons that he had to transform Alcoa but ordering people around was not his forte and it was bound to fail. He says he chose to focus on one thing and start disrupting the habits around it, which would in turn spread throughout the company.

This phenomenon is fondly referred to by the authors as a "keystone habit" - this is a habit that causes a chain reaction for disrupting habits. O'Neill learnt to recognize how institutional habits governed processes during his tenure as a federal government employee. He used this experience to introduce a better habit loop at Alcoa.

Whenever an injury occured' Paul required the unit president to provide him, within 24 hours, with a report and an action plan that countered and prevented its future occurence. Compliance with these new routine resulted in promotion for the unit president. In so doing, O'Neill set a cue (injury) and aligned it to a routine (reporting within 24 hours) which resulted in a reward (promotion), thereby completing the habit-loop.

A unit president could only meet the strict 24-hour deadline; he or she needed to to hear about an injury from his Vice President who was in constant communication with floor managers. These floor managers relied on workers for suggestions about safety. With time, the patterns shifted to meet the requirements and subsequently other aspects of the company also started to change quickly translating to an increased efficiency and quality.

A lot of keystone habits exist in various areas of life which lead to wider shifts in our behaviours. An example is people who begin a habit of exercise which make them to naturally start eating better, become more productive and feeling less stress. There is a vast chasm between understanding and applying this principle. Identifying a keystone habit takes a trial-an-error approach, with the aim of finding a "small win" - as the authors call it. Small wins are minor advantages that set into motion patterns bearing a larger impact.

A 2009 weight loss study, for example, found one such "small win" when researchers instructed a group of participants to make lifestyle changes apart from keeping a daily food log on what they ate. They naturally identified patterns that made therm want to plan ahead of their meals, and in turn led to healthier food. The group which kept a food log lost twice as much weight as other participants of the study.

5: Starbucks and the Habit of Success: When Willpower Becomes Automatic

One essential ingredient for success is willpower, more so than intelligence. In a 1950s Stanford study, researchers asked four-year olds sat on a table with a marshmallow that they could eat it immediately, or wait for the researchers to return in 15 minutes and earn another marshmallow. The researchers later tracked down the kids in high school, and observed that the ones who had self-control enough to earn an extra marshmallow at four years now had attained better grades, higher SAT scores, and general social success.

Another study from the 1990s illustrates the fact that we all have a limited supply of willpower. In the Case Western Study, researchers instructed a group of students to skip a meal and then sat them in front of two bowls, one had fresh, chocolate chip cookies, and the other contained less appetizing radishes. Half of the students were told to eat only the cookies and the other half, only the radishes before giving them an impossible puzzle.

We also know that we all have a limited supply of willpower. In a Case Western study from the 1990s, researchers instructed a group of undergraduate students to skip a meal, then sat them down together, each one in front of two bowls. One bowl contained fresh, delicious chocolate chip cookies, while the other held somewhat less appetizing radishes.

Half were told to eat only the cookies, and the others were told to only eat the radishes. The researchers then gave the students an impossible puzzle to complete. While none of them knew that the puzzle was impossible, the ones who had radishes gave up earlier - in an average eight minutes, than the ones that had eaten cookies -an average of nineteen minutes of perseverance. The disparity in perseverance between these two groups is best explained by the depletion of willpower for the radish-eaters when they had to resist cookies.

Additional numerous studies have shown that exercising willpower in one focus area, like academics or exercise, will increase one's reserve willpower they can apply to life's other areas. Neither of these things is sufficient to exercise enough willpower consistently. The success of coffee chain Starbucks is centred on methodical planning of a routine for those cues (inflections) where temptation and pain are strongest.

Starbucks have a tailored training system that guides employees through identification of inflection points and matching them to one of the coffee chain's dozens of routines. An example of such an inflection is when a customer is angry and yells for getting the wrong drink. By choosing a certain cue ahead of time, willpower grows into a habit, and employees can then provide a high level of service that leads to a routine of customers coming back frequently for expensive lattes.

Starbucks also encourages its employees to employ their intellect and creativity, a key ingredient to its success. Students at the University of Albany were put in front of a tray of cookies and the researchers nicely asked a half of them not to eat the cookies and explained the purpose of the experiment while in the other half, they did not explain to them the purpose of the experiment. The first group later outperformed the second group significantly in an unrelated standardized focus test.

When people feel that they are doing something out of personal choice and understand the purpose, they perform far better and exhibit much greater willpower. Willpower becomes more difficult when people are just following orders.

Chapter 6: The Power of a Crisis: How Leaders Create Habits Through Accident and Design

The author argues that all organizations are characterized by institutional habits; they have unspoken routines that operationalize them. Lack of these habits would render leading the business a difficult task as the managers would not be able to keep up with the complexities of all the permutations of decision making presented to frontline workers on a daily basis. Dozens of convergent processes, habits, and behaviors are responsible more for an organization's decisions than formal research and development processes.

It is unlikely that one would point their colleague to the company handbook when asked about how to succeed at the workplace. Instead, one is more likely to educate them about informal rules, truces and lines that should not be crossed.

In the case of workers in a successful organization, it is likely that the company cultivates organizational habits providing a balance of power, freedom and keeping it clear who is in charge.

Rhode Island Hospital was considered to be one of the best medical institutions in the early 2000s, but a toxic culture of arrogant doctors mistreating nurses led to a series of tragic operating room mistakes, and negative publicity. Rhode Island Hospital became the poster child for mistakes and a target for local and national media, a genuine crisis requiring implementation of previously unimplemented proposed changes.

Operating rooms had video cameras installed in them, checklists mandated for each surgery, and an anonymous reporting system was implemented. The new changes, in addition to new training systems empowered nurses to prevent operating room mistakes. The hospital has, as a result, earned prestigious awards for quality care.

Chapter 7: How Target Knows What You Want Before You Do: When Companies Predict (and Manipulate) Habits

Over the past twenty years, companies have begun to rely heavily on big data in an attempt to predict the customer's buying habits. A big lesson from this is the realization that most buyers make decisions to purchase the moment they see a product. Habits have proved to be stronger than pre-written grocery shopping lists in spite of a shopper's intentions. One difficult problem for the companies however, is that these habits are unique to each customer and there is no one-size-fits-all sales or marketing techniques to it.

With a view to solving this conundrum, companies like Target have collected individualized shopping data for the past decade through loyalty, credit, rewards, and frequent shopper cards. If they combine all this with easily purchasable data about one's age, marital status, ethnicity, location, and so on, they have an incredible detailed picture of one's identity and what is going on in their life.

Target, for instance, knows that someone who purchases Popsicles almost once a week at around 6:30 on a weekday, and mega sized trash bags every July and October probably has kids and has a lawn to mow during summer and a rake for leaves during the fall.

The case is similar if you buy cereal and never milk from a retail store as the algorithms will take note that you probably buy milk elsewhere. It will not be long before milk coupons and school supplies coupons start hitting your mailbox as well as coupons for lawn furniture. Meanwhile your across-the-street neighbor could be receiving a whole lot of different coupons.

Companies using this advanced data mining techniques have found out something crucial for their marketing success: people often change their purchasing habits when they go through major life events such as a job change, child birth, move, or relationship change. They are really good at this and as soon as you are pregnant, you will see diaper and maternity clothes coupons sandwiched in between your beer and lawn mower ads.

This similar technique is now popular at radio stations when introducing and popularizing new songs. Outkast’s song, "Hey Ya!" became a flop when it first aired despite music executives loving it and it hitting all the right algorithmic metrics. However, almost a third of listeners would switch stations within 30 seconds of the song being payed. At the time, the music industry had started realizing a fundamental hard truth about how people relate to music - listeners cared more about the familiarity of a song than quality.

In an early 2000s research, male listeners claimed they hated Celine Dion but stayed tuned whenever her songs went on air. The brain naturally processes music to hone in on familiarity and patterns and therefore, it is our subconscious habits and not our preferences that dictate what we listen to.

With this realization beginning to set in, radio stations recognized that Outkast's tune, "Hey Ya!" was probably failing because it was not similar to other songs in the Top 40 and began sandwiching it between two familiar songs. This move cemented the song's position in an already existing habit loop in listeners' minds which pushed the song to 5.5 million album sales and a Grammy Award to boot.

The take home lesson here is that industries do not simply manipulate our habits but instead, use a supremely powerful tool by sandwiching a new habit between our existing routines.

Part Three: The Habits of Societies

Chapter 8: Saddleback Church and the Montgomery Bus Boycott: How Movements Happen

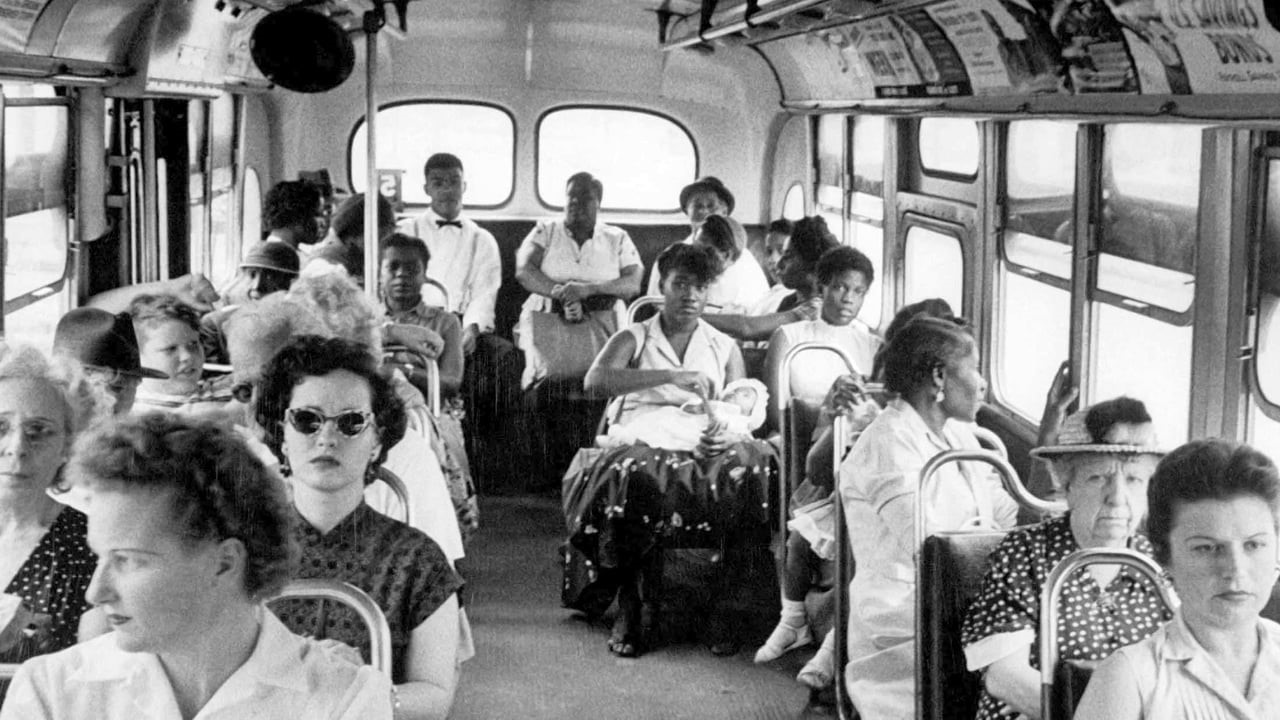

On Thursday, December 1, 1955 at 6:00, Rosa Parks, now an American hero, courageously uttered her famous refusal to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus. Contrary to a commonly held belief, she did not seat in the "white section," and the white man openly had three empty seats to choose from. While Mrs. Parks wasn't the pioneer of this defiance, - within the past few months, there had been two similar incidents - she is the one who sparked the civil rights crusaders, and habits were responsible.

Rosa Parks was deeply involved in the community. She was affiliated with dozens of social, religious, charity, and hobbyist groups that had no venue to contact one another. It all began when a white lawyer and the former head of NAACP Montgomery, both Mrs. Parks’ friends, posted her bail and requested her to use the incident to legally challenge Montgomery city's segregationist laws.

By the end of the day, the community had already heard about Mrs. Parks' arrest and an influential group comprised of school teachers had suggested a boycott on the day of Rosa's date with the courts.

The various groups immediately began to print and distribute flyers, spreading the word even further in a span of just one day. Not only did they leaders know Rosa, but hundreds of individual members of the groups knew and considered her a friend as well.

These were people who, months before the incident on the Montgomery bus, patiently endured the gross indignities of a silently racist legal system which had previously ignored similar injustices. This background explains why these people were now up in arms responding to the call, in defense of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

Rosa did not have thousands of friends as we might be tempted to believe but sociologists use the term, "weak ties" to describe her situation. Weak ties tend to be more important than close friends in many ways. They tend to be more valuable in connecting us to groups and information that we otherwise cannot find out by ourselves.

In the Montgomery bus incident, weak ties were powerful as they effectively created peer pressure. It is common sense that most people would not jump to inconvenience themselves seriously for a loose acquaintance like Mrs. Parks, but her web of connections created euphoria of peer pressure.

One risked losing social standing in the community by failure to participate in the boycott in solidarity with Rosa. When the Montgomery city paper published an article about the black community’s planned boycott of the buses, it served as social proof that everyone was doing it. The boycott emerged as a new social habit that spilled into larger social habits of peaceful protest, culminating in the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Chapter 9: The Neurology of Free Will: Are We Responsible for Our Habits?

A cognitive neuro-scientist discovered something fascinating in 2010 when he compares the brains of pathological gamblers against social gamblers using an MRI machine. Watching the slots roll on a video, the pathological gamblers' brains registered more excitement when a winning match displayed. Of interest however, is that social gamblers registered near misses correctly as losses, while pathological gamblers registered near losses as wins.

This difference in the habit loop is crucially different as the pathological gamblers' mind provides a reward after a near Miss, resulting in a habit loop that leads to more gambling. A similar cue in a social gambler's mind only results in a reward when they stop gambling and escapes losing money. This subtle difference in the habit loops among the two sets of gamblers is responsible for the industry's profitability and ruining of lives.

The author also questions the morality of holding pathological gamblers responsible for their actions. However, he argues that no matter how strong a habit is, provided you are aware of its existence, you have the power to decide to change it.

Duhigg then recounts a story told by an author named, David Foster Wallace: “There are these two-young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’”

The young fish swim for a little bit before one asks the other what "water" actually is. Just like the fish, most of our lives are riddled with habits that we don't even realize exist.

APPENDIX

A Reader’s Guide to Using These Ideas

The appendix section is tailored in a special way to help the reader apply the techniques highlighted throughout the book. This makes The Power of Habit unique for having the appendix as the best section of the book. It helps us see that we have been immersed in various habits our whole lives, and we can begin shaping them at our will. By following this set formula, we can change our most undesirable habits:

1) Identify the routine - it may not be often obvious but it is usually easier identifying the habit that you want to change.

2) Experiment with rewards: for you to be able to pinpoint a cue, you need to experiment with rewards such that everytime you feel an urge to complete a routine, you try a new reward. An example is if you are trying to cut down on junk food, you can try an apple or coffee instead. To test for a cue, you can set a timer, say fifteen minutes, and when it goes off ask yourself whether you still have the urge to eat junk food. If you were hungry, an apple would suffice but if you were just tired, coffee should help.

3) Isolate the cue - when you identify the reward that satisfies the cue, you still have to identify exactly what the cue is. Most of the habitual cues fall into five categories:

- Location

- Time

- Emotional state

- Other people

- An immediately preceding action

4) Have a plan - when you recognize the precise routine, reward, and cue, it will be easy to designate different routine to counter your habits and but provides the same reward after the same cue.

Keep alert for the cue and act out your present routine. If the cue is time-based, set an automatic alert for it. Should this work, you've confirmed that you found the right cue-rward pair, and your habit can then be easily altered.

Conclusion

The Power of Habit is an interesting read which revealed to me that most of what we do relies heavily on habits. Furthermore, our abilities to identify, reshape and build our habits are integral to personal growth and life's endeavors.

Much of the self-improvement crowd obsesses a lot about assigning importance to willpower, goals, and other facets but the more we understand habits, we will realize that it is an anchor to changing all these facets. We can indeed increase will power through exercise and our goals help is to focus our efforts and checking out our progress as we strive to attain them.

Generally this is a good read for those trying to find practical techniques to implement and is made more exciting by the book's narrative style. In deed, the key to getting rid of the habits that keep holding you back from jump-starting your potential like deep within this book.