Candid Interview with the Guy Who "Failed to Build a $1 Billion Company" (Gumroad Founder, Sahil Lavingia)

Image credit: articlelist.com

This is the second in our How We Made It in Ecommerce series. Sahil Lavingia is the founder of Gumroad, an ecommerce platform that allows creators to monetize their wares. To date Gumroad has paid out more than $180 million to creators.

Our first interview was with Trina Felber, the founder of Primal Life Organics. Our next will be with Mike Faith, the founder & CEO of Headsets.com a $70 million plus ecommerce company. We will soon start publishing the accompanying podcasts as well. To receive our new stories sign up on the black opt-in bar above.

Sahil Lavingia once thought success meant building a billion-dollar company. One very public failure later, he considers himself successful for completely different reasons.

“Money is money,” Lavingia says. “My experiences that I’ve been able to have, and this path, have been pretty great.” Gumroad will never be worth a billion dollars, but Lavingia is content to run it as a smaller company with no plans for scaling up. How did he go from billion-dollar dreams to this relaxed acceptance?

Once upon a time, Lavingia was the second employee at Pinterest -- a company now valued at $12 billion, and rumored to be going public this year. He left Pinterest before his options vested hut he doesn’t look back on the decision to leave wistfully. “I think regrets are mostly a waste of time,” he says. “I try not to think too much in hypotheticals.”

That same attitude helped him turn what many would call a start-up failure into an unconventional success.

“The older you get, the more you realize that your net worth is not really what’s going to get you excited about doing whatever you’re doing,” he says. Not only that, but you can’t control money: one of Lavingia’s most important lessons was learning that hard work doesn’t always equal a bigger net worth.

These lessons all came from the meteoric rise, and subsequent steep fall, of Lavingia’s first startup: Gumroad.

Gumroad, an ecommerce platform for selling products from software to art, was born out of Lavingia’s own needs. He wanted to sell a product that he had made: a pencil icon designed with Photoshop. But he discovered that there was no easy way to sell it, so he decided to create a way.

“If I wanted to give it away for free, there were so many different services that I could use to go do that. But the minute I wanted to charge anything for it -- it didn’t really matter how little, a dollar, for example -- it became super difficult.” He’d have to navigate credit card processing and everything else on his own if he wanted to sell his product. Other creators, he suspected, faced the same challenge.

So Gumroad started with this question: How easy can we make it for someone to sell something?

“If people want to make stuff, we want to make it really easy for them to sell that stuff, so they can focus on making stuff,” Lavingia says, “which for most creators is a much more enjoyable part of their lives than dealing with the actual commerce part.”

Lavingia jumped right into building his business, without even deliberating on the name. “I built the thing and I needed a name,” he says, “and I just went through my list of domains that I had registered over the years, and it was one of the few that was generic enough that it fit the purpose.” Once a brand becomes successful, he believes, any name can seem right.

Success looked like it would be a cinch for Gumroad. Lavingia quickly raised over a million dollars from angel investors and VC firms in the first round of funding. Just a few months later, his team raised seven million more, led by a major VC firm. It was his first startup: he’d had many prior ideas, but Gumroad was the first one that looked like a viable company.

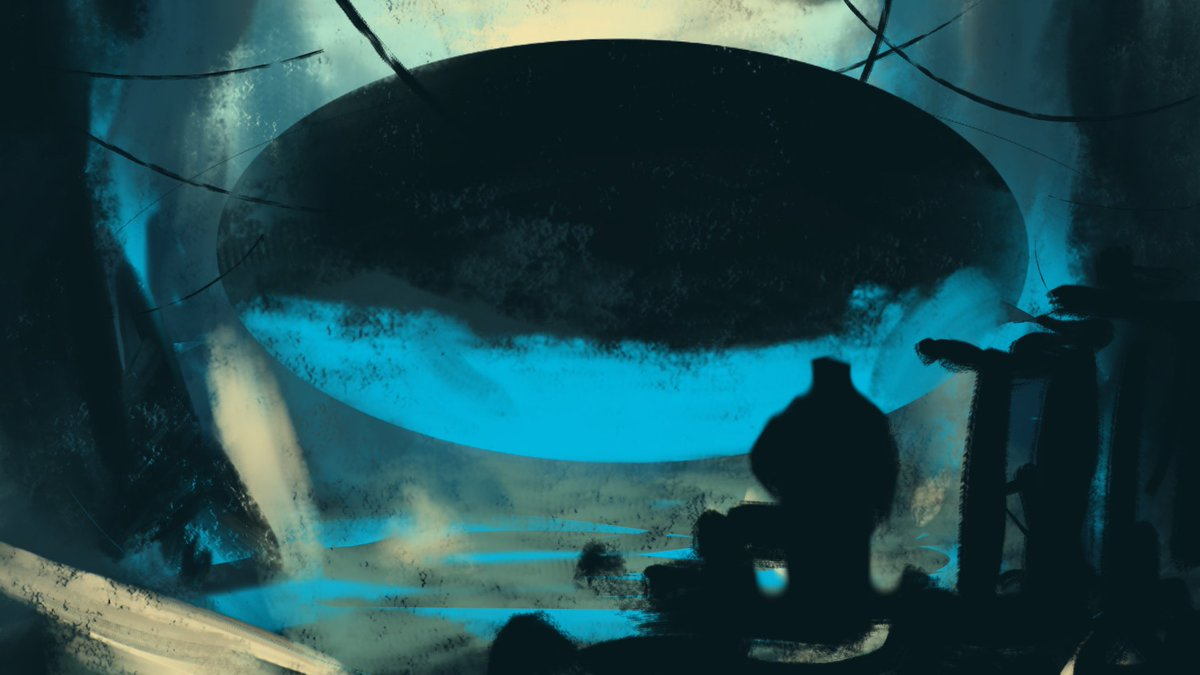

Image credit: businessinsider.com The Gumroad team after raising $7 million from top tier venture capital firms.

Although people often compare Gumroad to online marketplaces like Etsy, the startup differentiated itself in crucial ways. “We’re mostly traditional content -- we’re a lot of software, a lot of videos, a lot of documentaries,” Lavingia says. Etsy, on the other hand, primarily involves handmade physical products.

“If people want to make stuff, we want to make it really easy for them to sell that stuff.”

Gumroad also isn’t a marketplace: it’s an ecommerce platform. People who want to use it have to find their own audience to sell to. Gumroad just helps them monetize that audience.

The value of the idea was clear, and Gumroad’s growth was fast -- until one day, it wasn’t.

Lavingia quickly laid off most of his team to try to keep things profitable. But the layoffs were publicized by TechCrunch, starting a downward spiral of public failure with Lavingia at the center. (For the details of Gumroad’s rise and fall, check out his viral Medium post.)

Shutting down the business and starting something from scratch seemed like the wise thing to do. But Lavingia felt responsible to the creators that used his platform, even more than to the investors who’d helped build it. He had built something to help a group of people solve a problem, and even as Gumroad struggled, that goal remained Lavingia’s primary focus.

Even the employees he had to lay off agreed that keeping the company going was the right thing to do. “That was the priority stack: creators, or customers, were first. We were building for them,” he recalls. Lavingia wasn’t willing to cut his customers off from the profits they made using Gumroad. “The company wasn’t successful, but the product was.”

Keeping the company going required Lavingia to put in 16-hour days for months. To his surprise, it paid off: the business was going to stay afloat. And after pulling off this recovery, Lavingia was able to reduce his time spent running the company to a minimum.

Although Gumroad would never reach the billion-dollar status he’d once dreamed of, it was functioning, and supporting the livelihoods of the creators who used it.

Part of the reason the platform still works so well is that it naturally lends itself to organic marketing. At first, Lavingia found users through cold calls and emails -- lots of them. “At the beginning, no one really knows who you are,” he says. He had to convince people to take on the risk of trying new software.

But once he’d gotten some people to try Gumroad, things became easier. Today, his team no longer has to work to source customers. “Over time, the organic stuff just happened. You can’t really force it,” Lavingia says. If you already have users who like your product, finding more of them comes naturally.

Gumroad doesn’t use SEO or paid marketing tactics like Facebook ads. While Lavingia knows those methods work, his product doesn’t need this kind of support. “To sell a product on Gumroad, you have to tell your audience about it,” he says. This translates into a consistent source of organic marketing for the brand.

That’s why, even as Lavingia laid off most of his team, Gumroad itself kept growing. Lavingia couldn’t control that growth for better or worse: there was no way to “growth hack” the business for exponentially bigger numbers. But the growth stayed steady even through the company’s worst days.

Seeing the growth, but not being able to spur it higher, was both exciting and disheartening. “Markets are big things,” Lavingia says, “and I think they’re easy to ignore.” He believes it’s valuable for entrepreneurs to learn that you can’t bend a market to your whims, no matter how much you may want to.

But accepting what he couldn’t change allowed Lavingia to relax into the realities of running a small but viable business. Today, the brand is easy to manage. Gumroad relies on the software development platform Github, but otherwise doesn’t require many tools to run smoothly.

When Gumroad was bigger, Lavingia used the management software Asana to stay organized, but right now the business doesn’t even need that. He also loves Twitter for its ability to provide a track record of the brand’s history.

Still, Lavingia believes that most business software is overrated. Keeping it simple works best. “Just use the basic stuff first,” he suggests. “Use the thing that other people are using.” Otherwise, brands run the risk of alienating new employees by using complicated technologies that new hires need to learn.

However, he does wish he could find the right software to help manage his current team, which is now remote. “As we grow the company, I’m excited about it, but I definitely can see the pains already,” he says. Now that more companies rely on remote teams, there’s a clear need for tools to help brands stay organized without an office.

Lavingia also recognizes the difficulties that are unique to running a small company with no intent of growth. In the future, he expects to see more tools that will help small brands automate systems from support to sales to social media management.

Today, some of Lavingia’s side projects relate to solving these kinds of problems. But his other side projects are completely unrelated to business. One of Lavingia’s favorite hobbies is painting: he spends about 18 hours a week doing it. “If I have a really great painting, I celebrate it. If I don’t, I celebrate it,” he says. “It’s about this multi-year journey for me, improving my ability to paint.”

Some of Sahil's paintings. As a creator himself, he understands his customers deeply.

That same attitude carries over into his entrepreneurial life. “I don’t measure my success, I just measure what I’m doing. It’s more about this sort of holistic growth over time.” He believes that intense self-criticism, whether in art or in business, will only get in the way of success.

Your first company may never be perfect, but you have to start somewhere, Lavingia says. “There’s nothing that’s gonna teach you how to build stuff faster than building stuff. It’s just like painting.” If you’re doing the work, you’re succeeding.

Elyse is writes for Capital & Growth. She is aspiring novelist.